Our Family History

Our Family History Our Family History

Our Family History

by Rosemary Enthoven

(daughter of Eleanor (O'Brien) Fenech, Martha (O'Brien) Marion's oldest sister)

This is the history of your family as my sister, Anne, and I have learned it from our parents and from our grandparents. Like so many American families, we carry in our bodies and in our bones the spirits of several nations and the cultures of far away lands. Even when we are not aware of their echoing voices in ourselves, those voices are a part of our deepest selves. If we know this past, even a little of it, it can enrich and amaze us and inform and inspire our travels. When we look at our little children, we will have the fun of seeing an old talent or a puckish smile come to light again. This is the story of my inheritance and that of my sister, as best we know and can tell it.

The Irish Side: Maternal Great-Grandparents

Our mother, Eleanor, was born in

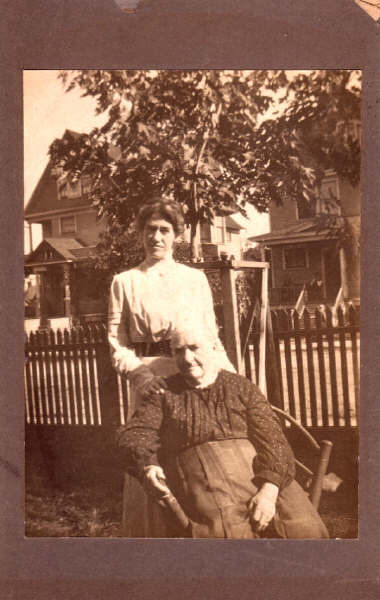

Mary Green (seen sitting at right with daughter Hanna -- later called "Auntie" -- circa 1912), my great-grandmother, was born in 1836 in County Cork, the southernmost county in Ireland. She left home all alone at the age of 17, and sailed to

Some Irish History

It was a complex series of events over several centuries that caused so many of the Irish people to emigrate to the

In the 17th Century,

Oliver Cromwell and then William of Orange, who became King William III of

The lives of our great-grandmother and the lives of all Irish were changed irrevocably by the Penal Laws which were imposed on Catholic Ireland in the aftermath of the

In 1845, the potato crop in

For the next decade, families and villages were wiped out by famine. Parents gave their last food to their children; children wandered as orphans through the countryside. Workhouses were everywhere, but there was no work, and landowners took to paying their tenants to emigrate (10 pounds was the cost of passage to

The Voyage To

The Voyage To

By 1855, one million Irish had sailed to distant lands, and by 1880, another five hundred thousand. This was the time

The Famine Ships

Now we can picture Mary in 1853 with her small bag of provisions and maybe some extra clothes going down to the wharf at

The voyage on these small sailing ships took from five to eight weeks. I remember my great aunt Annie telling me it took Mary six weeks to reach

Life in

Mary must have been very strong and very determined to survive all this, but survive she did and arrived safely in

"The man Mary married was Patrick O'Brien. He was a man not much older than Mary, born in

He came to

"I am toying with the idea of coming to

I really don't know much about my great grandfather, Patrick O'Brien. He looks a handsome, strong man from his photos, and I like to think that both Mary and Patrick were strong, and possibly excited about all that was new and promising in

Mary and Patrick married in

They must have loved stories, and humor, for certainly my grandfather had a wonderful sense of humor, and all my great uncles and aunts were exceptionally affectionate and generous, "not a mean bone in their bodies" was the way it was put. They must have gotten these qualities from somewhere, and I expect it was from Mary and Patrick who sat on the steps of

I am not too sure of what happened to Patrick and Mary then. I do know that they were married in

Moving To

Instead of raising their children in the Irish Catholic ghettos of Boston, they brought them out to a territory with greater freedom, greater opportunity for hardworking families, more ethnic diversity, education, and a whole new world to explore. As you hear the story, you will see what wonderful advantage they took of this undeveloped rural land which must have looked a little bit like

A letter from a Welshman written from mines in

This is the world that Patrick and Mary journeyed to with high hopes and heavy hearts as they left those little graves in

Life in Copper Country,

Eventually, Patrick and Mary must have secured a home and a job in the mine for Patrick. They must have been overjoyed to finally have children who lived and who prospered in their new little world, but there was still sadness to come. Accidents, illness, deaths of infants and mothers were a part of their world in ways that we can hardly appreciate now. Doctors and medicines would have been very sparse in northern

Of their children, these are the ones that survived beyond infancy. Records of their births survive in the 1870 and 1880 Census tracts for

- Daniel, born in 1859...He died in a mining accident.

- Mary Ellen, born in 1861...She died in 1878 at the age of 17.

- Timothy, born in 1864.

- Patrick Jr., born in 1867.

- James, born in 1870.

- Hanna born in 1872 ...Known as Annie, or to our generation as Auntie.

- Michael Edward, born in 1877...My grandfather.

Sadly, I do not know very much about their early lives. It can be freezing cold in northern

Swedes and Finns, Polish and Hungarians, Scots and Welsh, Grandpa seemed to know them all and find great pleasure and even humor in their stories and ways of speaking. One gets the sense from his letters and from knowing him later, that there was easy tolerance among these many ethnic groups, and the Irish must have found it a great relief not to be persecuted for their beliefs or looked down upon for their culture. There were public schools for all, and churches, and a lively community spirit.

Life in the mining villages was harsh as well. I wonder if the small houses had electricity or running water. The impression I had from Grandpa was that life was not easy, but marked with an independence and a sense of mobility and freedom that must have been exhilarating.

But overall, in those early days loomed the Mine -- the source of jobs and income, the source of danger and death. Our own family suffered tragically in this mine. My great grandfather Patrick and his son, Daniel died in mine accidents. Son Patrick was in law School at the time in

Grandpa tells the story of Daniel's death

in a letter to Jacqueline Enthoven in November, 1959...

"As regards family history........ I am thinking of many things I will include

in the memoirs. I will be helped by a book I got from Judd and Kitty McCluskey on my birthday, Sept. It is a history of the Calumet and

I do know that after this accident, my great grandmother did not want any more of her children to go into the mine, and as far as I know, they never did.

I do not know what happened to Uncle Tim, but Patrick or Uncle P.H., as he was always called, studied Law in

Uncle Jim never married and was a bit of a wanderer. I remember his "dropping in" on us several times to stay, once on his way back from

Aunt Annie, whom we always called "Auntie," was wonderful, my favorite of all my many relatives. She had trained as a nursery school teacher, I think in

I still remember so many of her songs, "Up on the housetop" and "Little dog Scottie with tail so short" and the story of "Good little Nell who rocked the baby and cleaned the house." Auntie spent the last months of her life at our house on

And then there was my grandfather, Michael Edward O'Brien. He was a tall, imposing figure, rather heavy in his later years, who loved a good dinner and a good story. He was definitely a people person, generous, outgoing and demonstrative. He graduated from high school but probably was not able to go on to college. His own father died when he was only 13, so he might have left school early to help to support his mother and sister.

He worked for the post office as a young man in Laurium, and then discovered the world of life insurance. Life insurance was a new idea at the turn of the century. There was no social security, and company pensions were not ordinary. There was some accident compensation paid for by some companies , but if the breadwinner of a family died through illness or accident, the widow and children often had no secure means of income. Thus, life insurance can be very appealing to a young man with a family in times when illness and accidents were so prevalent. I will tell more of this when I speak of Uncle P.H.'s courageous career in gaining benefits for families of miners.

Somehow, Grandpa was hired by a company that sold life insurance, and he went all over the state talking men into gaining "peace of mind" and the price of the premium, assuring them that their families would be provided for if they could no longer provide. Since his own father had died in the mines, grandpa knew from experience how devastating an accident can be for a family.

With Grandpa's gregarious nature and energy, and his connections with ethnic groups all over the state, he soon became one of the most successful salesmen in

MICHAEL O'BRIEN MARRIES NELLIE HARRINGTON

First, Grandpa fell in love with Nellie Harrington who had grown up in

She was the seventh of 13 children. Her parents were Sylvester Harrington and Mary Shea. We have a photo of Mary Shea. Amazingly enough, if I heard the story correctly, our grandmother, Nellie had gone off to

Grandpa said that he first saw Nellie in Church at Christmastime, and fell in love with her immediately. She was so beautiful, he said. All the photos of her show her to be lovely, indeed, calm and intelligent. She had large eyes and long face, her hair and clothes seem quite stylish. I am sure that Grandpa loved her with a passion, and was always bringing her presents and flowers. That was his nature.

MY MOTHER'S EARLY YEARS

My mother, Eleanor Mary was born on September 20, 1904. When my mother was eight years old -- and already had four little sisters, Anne, Kitty, Margaret, and Martha and a little brother, John -- Grandpa moved the family to

And then the worst of all possible things happened. My grandmother died totally unexpectedly. There was no illness, and no warning.

My father told me many years later that he suspected that she died of an ectopic pregnancy, although that could not be proven. Later my mother had an ectopic pregnancy, and my father never lost his fear that she might suffer another.

My mother always gave the impression of having had a secure, comfortable, and happy childhood. The children went to the local parochial school, and summered in a cottage at

But besides the carefree times, mother told us about the weeks of confinement the children would have when one or the other of them contracted a disease like measles or mumps or chicken pox. If one child came down with the virus, the whole family was kept in quarantine. That could last for weeks, as one child after another contracted the disease. My grandfather usually moved into a hotel during those weeks, as otherwise, he would not have been allowed to go back and forth to his office. For the children, it was a long holiday where if they were not the current patients, they amused themselves by giving plays, playing wild games of hide and seek, leaning out windows, etc. It must have been a very trying time for the adults of the family trying to contain all the exuberant energy of the well children while nursing the sick ones, and who with so little medicine, could be very sick indeed.

In 1917, this idyllic childhood ended very abruptly with the death of my grandmother, the mother of this large family. My mother told us later that they had all gone off to school one morning, with no idea of a problem. They were called out of class early with the news that their mother had died. Mother said that they were given no explanation, and never really had a chance to talk about it or grieve. They were given black dresses for the funeral, that was all.

After that, my grandfather's sister, Annie O'Brien, came to stay and take care of the household and seven children. We called her Auntie, and I have written about her earlier in this account. My mother loved her for her gentle generous ways, but the sudden loss of her own mother I think cast a shadow of sadness over my mother for the rest of her life. My grandfather was deeply attached to his wife and suffered from depression in the months after her death. He went off to a sanatarium for several months, my mother told me, and later she went on trips with him to

Soon another sad death visited this family. Little Rosemary, the youngest of the children, and just six years at the time, died of diphtheria. Grandpa described her death in a letter written about 40 years after her death. The sorrow he still felt at losing this little child comes to us through the letter in the most moving way.

"She (Rosemary) was the youngest and was different, black hair and dark eyes, a regular little Spanish type. There was an anti-toxin for diphtheria, but instead of giving her a shot when he (the doctor) suspected it, he would wait until the next day to get a report from the Board of Health that confirmed his diagnosis. But in the meantime, all that day and through the long night, the power of the diphtheria infection was working although as the doctor admitted afterwards, it would have been no harm to give the dose of anti-toxin even though there was no diphtheria. She seemed to be getting better. The house was quarantined, so all I could do was to come to the back door and inquire how she was. My sister, Annie, was taking care of her with the utmost devotion."

I wish my mother were here to tell the story of her life as it unfolded. Despite these profound losses of a mother and dear sister, I believe my mother would say her teen years were happy ones. She recounted their summers at

Somewhere along in these years he married his first wife's sister. Her name was Lyle Harrington Kettenhofen. She was a widow with four children, Clemens and Bob, Mary and Bunny. So now there were ten children, all close in age and all teenagers or almost teenagers in one house. It must have been a household brimming with energy and activity. My mother was still the oldest, and probably always was a bit more responsible and reserved than the others, qualities she carried all her life.

I do not think that Grandpa and Aunt Lyle, as we called her, were very happy together. They never seemed close and had separate bedrooms as far as I know. Aunt Lyle died when I was in high school, and the step-sisters and -brothers never saw each other much after that.

The portraits of Anne and me, which we each have in our homes, and the four painting of a village along the coast of

I do not know what my mother did the year after graduating from high school. I believe it was another year before she started her training as a nurse at

"One never knows just what is around the corner. When Eleanor decided to take on training as a nurse at

Actually I don't think grandpa was quite right on his dates, as Mother did finish nurses' training, which took three years, graduated, and I think worked for a year or so as a public health nurse before marrying. Of course, she and my father couldn't marry before he had finished his residency in surgery and had established himself in a medical practice and income. That was the way it was in those days .

But Grandpa was very right that they were extraordinarily well suited and happy together. As I said at my father's memorial service..."She was the center, the quiet place where he could always come, the beautiful woman he loved above all things."

Our parents first lived at the Wardell in Detroit, just north of the DIA, an apartment-hotel rather near the hospital, and which must have provided many of the housekeeping services. Then they moved to a house on

From there, we moved to a house in

Of course, everybody walked to school in those days. Our mother had no car, and in fact, could not drive. Very few women could. She took the bus downtown to shop for clothes and household goods. Groceries were delivered to the door. My father went to the Eastern Market on Saturdays, bringing home bags of fresh fruits and vegetables, fresh eggs and flowers. I especially remember the gladiolas that he loved, and the plants of chrysanthemums.

It was in that house on Burns that we listened to our first electric Victrola, with 78 rpm records that seemed a miracle; that I broke my leg, falling down with my father on Easter eve. It was there that we strung a string to the Warren's house and sent paper messages back and forth; that Pearl Harbor happened and our father enlisted as an officer in the U.S. Army. He joined the medical unit from

It was in this house that Anne and I had polio in the summer of 1943, and spent weeks in bed, and more weeks learning to walk and run again. I will let Anne tell those stories as she was older than I, and has a better memory.